As someone who is an avid reader, a voracious writer and a science “nerd” in the extreme, I am always surprised when people say that the creative writing and hard science don’t mix. My initial reaction is to ask in disbelief,”Have you ever read anything by Michael Crichton? Does Jurassic Park ring a bell?!” One of my favorite authors, Michael Crichton, had an impressive command of scientific literacy as well as a profound ability in the nuanced art of writing fiction. Many people saw him as an anomaly, a man who had conflicting talents, but I think they go hand in hand.

The process of creative writing follows the scientific method astonishingly well. Great authors don’t just sit down and write whatever comes to mind. First you have to develop an idea. It might be a character, an alternate universe or a conflict. Then in your mind you try to work out the details surrounding this conflict. A lot of research goes into this step, because more often than not, your story will involve some topics you’re not an expert in. After you think you know what will happen, you sit down and write. As you run into problems, you have to revise your original ideas and often change the path of your story drastically. When you think you have something good, it has to go to an editor for “peer review”. Often they send it back to you with questions and suggestions to make the story more believable. Finally, your editor(s) have given you the go ahead to publish to a larger audience, allowing them to make of it what they will. Often this final story will spark follow up questions in your mind or the minds of your readers that lead to additional pieces of writing, either in the form of sequels or fan fiction, that start the process over to answer those additional questions. This directly models the scientific method we here at ACPHS are all too familiar with.

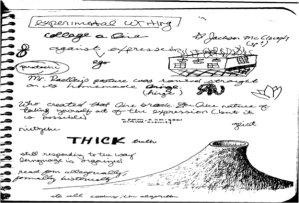

Additionally, writing is not a talent that you are born with. It is not something you either have or do not. In the same way you can improve your lab technique or improve your ability to solve a Calculus problem, you can also improve your ability to write. Being a good writer takes the same kind of work as being a good scientist. You take classes, learn new techniques and write a lot of drafts. You learn the rules and regulations that govern your language. You identify your weaknesses and practice them until they are no longer weaknesses. You recognize that there is always room to improve. The students I tutor in the writing center often preface their papers by apologizing. They tell me “they can’t write” as if this is some kind of innate character flaw they have no control over, but I don’t buy that. Writing is an experiment. It is a process of trials and errors to find your voice and the techniques that work best for you.

If there is one thing I could impress upon the incoming freshmen it would be that there is no such thing as something you “can’t” do in this curriculum. Most student come to this school thinking that they are good at science and therefore cannot be good at English too. But you were not born into this world blessed with the knowledge about biology and chemistry that you have now. Likewise, no one is born with the innate ability to communicate their thoughts and ideas effectively. Both of these things are things that are learned, in fact they are learned in very similar ways. Science and writing are not separate concepts; they are very closely intertwined. Neither one is a talent, but rather, they are learned abilities that anyone can master with enough work. So don’t tell me that you are a scientist who was never meant to write. Many schools call their writing center a writing lab for a reason. We are here to help you experiment with your writing so you can improve your technique and hopefully learn a new skill.